Understanding The Sino-Soviet Split

Beyond Ideology

Introduction

If we only look at surface events, it’s easy to reduce the Sino-Soviet split to a handful of familiar milestones: Stalin’s death, Khrushchev’s “secret speech,” the Great Leap Forward and the people’s communes, the public polemics, and the clashes over Zhenbao Island. In that simplified storyline, the break appears to be a matter of personality conflicts or ideological disagreements—as if, with a bit more tact or mutual understanding, Beijing and Moscow might have preserved their “comrades and brothers” relationship.

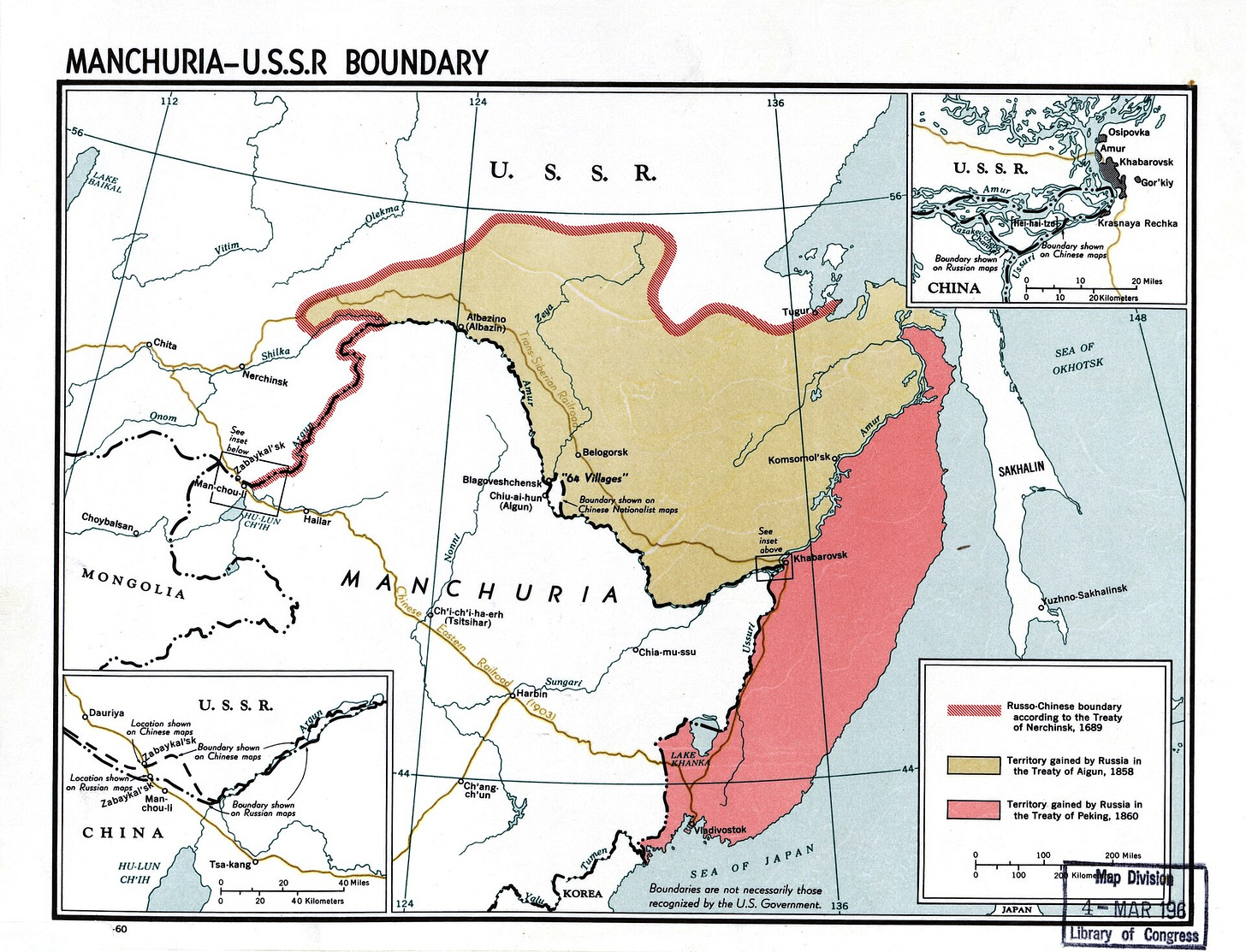

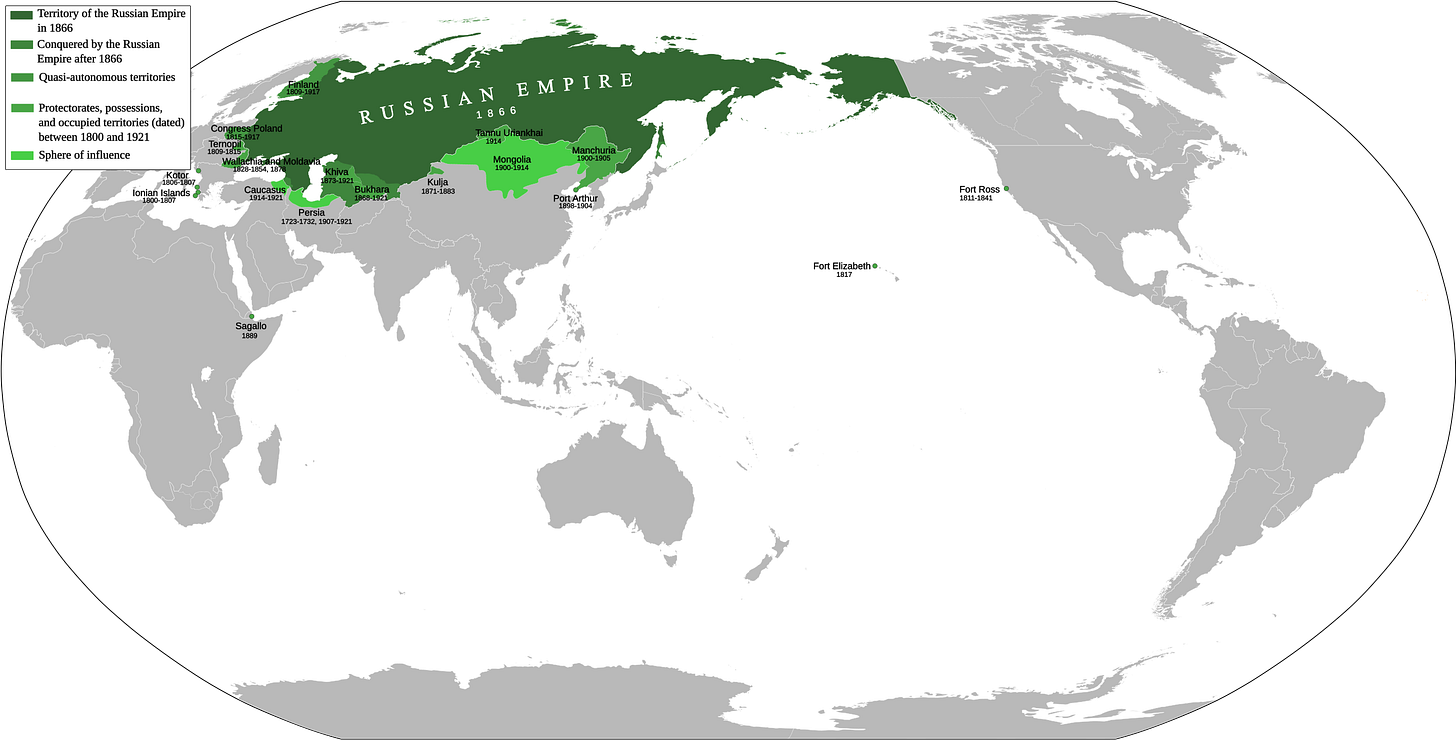

But a longer historical lens tells a harsher story. If we trace the timeline back from the twentieth century to the mid-nineteenth—from the Treaty of Aigun and the Treaty of Peking, through the status of Outer Mongolia, the Chinese Eastern Railway, Xinjiang, the postwar handover of Manchuria, Mao’s visit to the Soviet Union, the Korean War, Soviet aid, the CPSU’s 20th Congress, the Sino-Indian War, Mongolia’s missile deployments, Zhenbao Island, and the Vietnam War—one conclusion becomes unavoidable: the split was not an accident of diplomacy. It was the culmination of structural forces that had been building for a century.

At minimum, four layers of contradiction made stable partnership impossible:

1. Geopolitics.

Since 1858, China’s northern borders had been shaped under Russian military pressure. The pattern of unequal treaties, special privileges, and buffer zones did not disappear under Soviet rule; it merely received an ideological facelift.

2. Imperial inheritance.

The collapse of the Tsarist regime did not erase imperial strategic interests. In its dealings with China, the Soviet Union always acted both as “revolutionary mentor” and as a traditional border power—and those identities were never truly compatible.

3. Ideology and revolutionary leadership.

Who spoke for “true Marxism”? Who led the socialist world? Neither the CPSU nor the CPC was willing to subordinate itself to the other; fractures over ideological lines were only a matter of time.

4. Great-power security and status.

Once China industrialized and modernized its military, it was no longer content to remain under Soviet leadership. And the Soviet Union could not easily accept a rising socialist great power on its southern flank—one with its own nuclear weapons and its own strategic line.

In other words, the relationship was never a story of harmony suddenly turning sour. From the moment the two empires’ borders and interests began to collide, the basic trajectory was set. The so-called “brotherhood” was merely a chapter in a much longer script—not its ending.

This article does not aim to retell the history of Sino-Soviet relations in a conventional, chronological way. Instead, it connects a wide (though not exhaustive) range of events into a single analytical thread to illustrate one central argument: From the Treaty of Aigun to the Sino-Vietnamese War, the path was shaped by geopolitics, imperial legacies, ideological rivalry, and the security dynamics between a rising power and a status-quo one. The Sino-Soviet split was not a “friendship gone wrong,” but the natural outcome of structural contradictions reaching their limit.

The full piece is organized into seven parts. It begins with the Qing-era treaty system with Russia and the unequal borders that left China with a lingering sense of insecurity. It then follows the overlapping roles of “revolution” and “empire” in Soviet policy during the Republic of China era, through warlord politics, Xinjiang, and Outer Mongolia. From there, it turns to the Soviet occupation and return of Manchuria after World War II, where the CPC first confronted the realities of Soviet power. Next comes the high tide of the alliance—Mao’s Moscow visit, the Korean War, and Soviet assistance—alongside the early signs of strain. After that, the narrative shifts to the ideological rupture and nuclear disputes after the CPSU’s 20th Congress; the militarization of the border and the Zhenbao Island conflict; and finally, Sino-American rapprochement, the Soviet-Vietnamese alliance, and the Sino-Vietnamese War, which locked Sino-Soviet hostility firmly into the global Cold War.

Seen together, a slow but unmistakable arc emerges:

Unequal borders → Soviet inheritance of imperial logic → Postwar clashes of interest → Mutual control during the alliance → Leadership and ideological disputes → Border militarization → Proxy conflicts.

Through this lens, the Sino-Soviet split stops looking like a tragic misunderstanding and instead appears as the conclusion of a process set in motion as early as the nineteenth century.

And so the story begins—not in Moscow’s Red Square or at Tiananmen, but on a line drawn along the banks of the Heilongjiang River, in the northern China of the Treaty of Aigun and the Treaty of Peking.

Part One: The Memory of the Border (1858–1917)

From Imperial Expansion to the Logic of Buffer Zones

When examining the origins of later Sino-Soviet tensions, one fact is too often reduced to a footnote:

The modern Sino-Russian border was born out of a severely unequal power relationship.

It was not the product of balanced negotiation, but the result of Russia imposing a new geographical reality on a Qing Empire already weakened and unable to defend its northern frontier. The consequences of this asymmetry lasted more than a century. Whether Russia styled itself as an empire, a republic, or later a socialist state, its territorial outlook in the Far East and Central Asia carried an assumption of inherited privilege. China, by contrast—whether late Qing, Beiyang, Nationalist, or PRC—carried forward a deep psychological imprint of loss and insecurity.

This early imbalance shaped every later dispute: Outer Mongolia, Manchuria, Xinjiang, the Tumen River estuary, Zhenbao Island, and countless mid-river islands along the Amur and Ussuri. None were “sudden” issues; all were the slow unfolding of fault lines set in place during the final decades of the Qing.

To understand why the Sino-Soviet border became a frontline for tank armies in the 1960s—and why China reacted so strongly to Soviet missile deployments in Mongolia—we must begin here.

This chapter is not about indulging in late Qing victimhood. It asks a more fundamental question:

How did the border become a source of long-term structural distrust?

The Treaties of Aigun and Peking: Borders Etched Under Duress

The Treaties of Aigun (1858) and Peking (1860) may look like standard entries in diplomatic history, but they were among the most consequential turning points in the entire arc of Sino-Russian relations. They transferred vast territories north of the Amur and east of the Ussuri to Russian control, transforming what had once been a fluid frontier into a fixed line: Russia’s secure rear and China’s compressed northern boundary.

For Russia, this was one more step in a long march toward the Pacific. The Crimean War, Central Asian campaigns, and Westernization efforts had taught St. Petersburg that the Qing could no longer defend its old frontier. In classic imperial fashion, Russia formalized its gains with treaties.

For the Qing, these treaties were not “diplomacy” but concessions forced under military and political collapse: Taiping, Nian, fiscal insolvency, and the Western powers pressing at Tianjin and Beijing. When Russia stepped in as a “mediator,” the court had lost the ability to bargain; it could only plead for slightly smaller losses.

The aftermath created two enduring psychological realities:

For China: the north became a symbol of humiliation and permanent vulnerability.

For Russia: the Far Eastern territories became legitimate, inherited imperial possessions.

These mindsets survived into the Soviet era. Though the USSR proclaimed the abolition of unequal treaties, it never contemplated returning the Amur-Ussuri territories. China retained the memory of loss; the Soviet Union retained the territory. Every later dispute over even a minor river island carried the shadow of 1858–60.

The deeper lesson

Ideological solidarity could not erase the geography. A boundary drawn by imperial force would reappear, a century later, as the line between Soviet armies and the PLA.

The Ili Crisis and Russia’s Central Asian Order (1860–1881)

How Xinjiang Became the Prototype of a Buffer Zone

If Aigun and Peking defined the northeast, the Ili Crisis defined the northwest. Russia’s expansion into Central Asia and its temporary occupation of Ili during Xinjiang’s upheavals set the template for a new border logic—one that would persist from Tsarist rule through the Soviet era and into the Cold War.

Central Asia: Russia’s Imperial Boomtown

While Russia stalled against the Ottomans and European rivals, it advanced steadily in Central Asia, defeating the khanates of Khiva, Bukhara, and Kokand and folding their territories into a modern imperial administrative system. This ended the old, loose frontier structure that Qing rule had maintained and replaced it with a “state-to-state” border for the first time.

For Russia, Xinjiang became:

the southern shield of its Central Asian possessions,

a barrier against British influence via Afghanistan,

and a hinge for controlling Eurasian trade.

For China, Xinjiang was:

a distant, poorly governed, resource-draining frontier,

destabilized by rebellion and foreign meddling,

and perpetually vulnerable to being carved away.

Entering Ili: Intervention Under the Banner of “Security”

During the 1870s, as Xinjiang spiraled into chaos under Agubai’s regime, Russia marched into Ili claiming to “protect stability.” This was not straightforward annexation but a classic imperial maneuver: temporary occupation, administrative control, and the freedom to decide later whether to stay.

The logic was identical to what the Soviet Union later applied in Outer Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Manchuria.

The Treaty of Ili (1881): Humiliation With Strategic Logic

Though Chinese critics denounced the treaty as a catastrophe, Russia achieved what it wanted without the cost of annexation. What it sought was not sovereignty but a weak, semi-stable Xinjiang—a region China could not fully control and Russia could intervene in at will.

China, meanwhile, internalized a lasting lesson:

Whenever China was weak, Russia would enter Xinjiang.

That pattern would repeat itself well into the twentieth century.

Trade, Migration, and Control: The Northwest’s Structural Reality

In the late Qing, Xinjiang’s trade relied increasingly on Russian border cities and merchants. Consular authority, economic dominance, and cross-border networks allowed Russia to exert political influence disproportionate to its formal presence.

This pattern resurfaced in Soviet policy through:

economic control of Outer Mongolia,

trade dominance in Xinjiang,

and cross-border ethnic and migration networks.

The outcome was a durable pattern of memory on both sides:

For China: Xinjiang was a crisis boundary, not a secure border.

For Russia: Xinjiang was an intervention zone, not China’s exclusive domain.

This mutual perception would carry directly into PRC–Soviet relations.

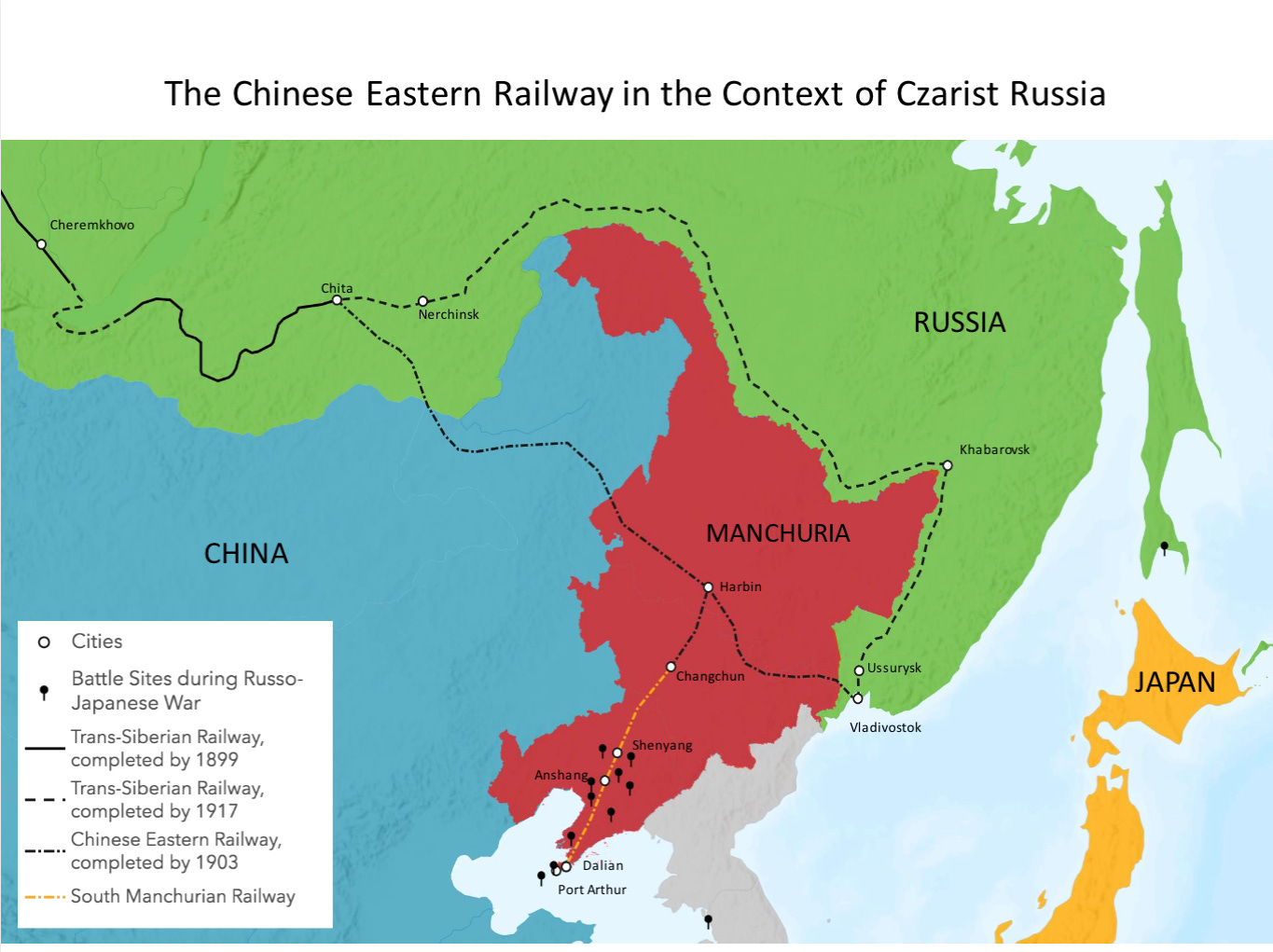

The Chinese Eastern Railway and the Russian Émigré Problem (1880–1911)

The Northeast as a Laboratory of Imperial Administration

If Xinjiang showed Russia’s method of exploiting instability, the Chinese Eastern Railway showed its ability to build durable, institutionalized influence. Unlike in Ili, here Russia constructed a full-fledged imperial presence, one that shaped future Soviet behavior in Manchuria.

Railway Surveying: Planning an Imperial Space

From the 1880s onward, Russian teams mapped mountains, rivers, and strategic routes across Manchuria. This was not simply infrastructure planning—it signaled that Russia regarded the region as integrable into its Far Eastern strategic system.

Later, this logic guided Soviet actions in 1945–46, when they rushed to take over the railways before anything else.

The 1896 Railway Contract: A Quasi-Colonial Corridor

Under the 1896 agreement, the Qing permitted Russia to build and administer a railway across Manchuria with its own police, courts, taxation, and settlements.

What emerged was:

A territory de jure Chinese but de facto Russian.

Russian administrative and legal institutions across the corridor.

Growing Russian émigré populations, especially in Harbin.

A regional economy oriented toward Russian markets.

This became the blueprint for later “joint management” policies the Soviet Union imposed in Manchuria.

Harbin: A Russian City Inside China

Harbin was not merely “influenced” by Russia—it was built as a transplanted Russian city, complete with Orthodox churches, Russian-language signage, foreign courts, and self-contained governance. For China, this created a structural wound: a major city that was culturally and institutionally outside Chinese control.

A Governance Model With a Long Afterlife

The extraterritorial administrative system surrounding the railway survived in Soviet thinking long after the empire’s fall. Even after 1949, Soviet approaches to Manchuria, Outer Mongolia, and Xinjiang reflected this belief that border regions were “special spaces” where normal rules of sovereignty did not fully apply.

From Empire to the Soviet Era: The Northeast as a Persistent Flashpoint

Japan’s takeover after 1905 did not change the pattern—only the actor. Manchuria became the site of an imperial relay: Russia → Japan → the Soviet Union. Through it all, China remained marginal to its own frontier.

This history left four long-term consequences:

Deep Chinese distrust of any Soviet “security arrangements” near the border.

Soviet institutional memory of special rights in Manchuria.

A paradox for the CPC: it rose to power partly in a space shaped by Russian institutions.

A strategic sensitivity that erupted in the 1960s border clashes.

The seeds of the Sino-Soviet split—especially in the northeast—were already planted.

The Prototype of Outer Mongolian Autonomy (1911–1917)

How a Buffer Zone Became Permanent

If the CER system defined Russia’s institutional presence in the northeast, the Outer Mongolia question defined its geopolitical strategy. Between 1911 and 1917, Russia established a semi-independent Outer Mongolia—nominally autonomous, practically dependent.

This arrangement became the DNA of the later Mongolian People’s Republic and one of the deepest structural contradictions in Sino-Soviet relations.

The Xinhai Revolution: A Window for Russian Influence

As the Qing collapsed, Outer Mongolian nobles sought a protector against instability and turned naturally to Russia, which offered security, religious protection, and preserved local privileges. China’s central authority had no ability to intervene.

Russia’s Strategy: A Cost-Free Buffer Zone

Outer Mongolia was valuable as a buffer, not as territory. Direct annexation was costly; semi-independence was cheap and effective. Russia aimed to:

Create a shield between itself and any future strong China.

Block Japanese expansion northward.

Protect its trade and religious networks.

This was “shadow suzerainty”—informal control without formal burden.

Autonomy Under Russian Protection

Outer Mongolia’s autonomy regime rested on a three-layered structure:

China’s suzerainty in name only,

Mongolia’s autonomous government in practice,

Russia’s military and economic patronage as the real determinant.

This was almost identical to the Soviet model after 1924.

Military Minimalism, Political Maximum Control

Russia needed only small garrisons, advisors, and control of key routes to dictate Mongolia’s direction. This “low-cost, high-control” approach became a template for later Soviet deployment in Mongolia and Xinjiang.

Economic, Legal, and Religious Russification

Russia reshaped three critical systems:

Trade shifted entirely toward Russia.

Religion (the lama system) gained Russian protection.

Law increasingly followed Russian consular jurisdictions.

By 1924, the Soviet Union barely had to exert effort; the groundwork was already laid.

Why Outer Mongolia Became the Deepest Sino-Soviet Fault Line

Outer Mongolia produced an enduring strategic contradiction that ideology could never solve:

For the Soviet Union: Mongolia was a non-negotiable security buffer.

For China: it was an unresolved historical loss embedded in national memory.

Their geopolitical psychologies were incompatible.

The issue vanished in the 1950s only to explode in the 1960s, when Soviet missiles appeared in Mongolia and border tensions flared.

The root problem was not Mao or Khrushchev—

it was the structure created in 1911–17.

Outer Mongolia became:

a late Qing failure,

a Beiyang impossibility,

a Soviet asset,

a CPC psychological burden,

a Cold War military flashpoint.

It was the single most intractable structural issue in the Sino-Soviet relationship—one that no amount of ideological affinity could erase.

Part Two: The Duality of Revolution and Empire (1917–1945)

Soviet Russia Between Ideals and Inheritance (1917–1924)

If the previous section explored the imperial structures Russia imposed on China before 1917, the Bolshevik Revolution seemed—at first glance—to promise a sweeping reversal. The Tsarist Empire collapsed, the Soviet state proclaimed itself anti-imperialist, and Moscow announced with great fanfare the “abolition of unequal treaties.” To many in China, this sounded like the dawn of a new, equal-era relationship.

But this idealistic vision clashed immediately with reality.

Regime change did not alter Russia’s geography, demography, or strategic environment. Transbaikalia was still Transbaikalia; Siberia remained Siberia; Outer Mongolia’s political institutions were still intertwined with Russia’s influence. None of this vanished with the Romanovs. As a result, Soviet policy toward China developed along two parallel tracks:

Ideologically, the Soviets presented themselves as a revolutionary state breaking from imperialism.

Geopolitically, they inherited the Tsarist Empire’s core strategic spaces.

Thus, from the outset, China and Soviet Russia were “comrades in rhetoric, neighbors in competition.” This duality—revolution versus empire—would ultimately become one of the fundamental causes of the Sino-Soviet split decades later.

The Promise to Abolish Unequal Treaties: Moral Declaration vs Strategic Reality

In November 1917, the new Soviet government announced that all unequal treaties with China, signed under the Tsars, were nullified. It was the first time a great power had voluntarily walked away from imperial privileges in China. Chinese intellectuals, revolutionaries, and even warlords reacted with excitement.

Yet the declaration was fundamentally symbolic.

The Soviet government lacked both the capacity and the incentive to undo the territorial and administrative structures it had inherited:

The lands north of the Amur were fully integrated into the Russian state.

Russia’s institutions in Manchuria were deeply embedded.

Outer Mongolia’s political order already leaned heavily toward Russian protection.

The Far East was engulfed in chaos: White forces, Japanese troops, and foreign interventionists all threatened Soviet survival.

Under these circumstances, a full renunciation of Tsarist legacies was impossible. The abolition statement projected an image of moral leadership, but it was not a commitment the Soviets could (or wished to) implement.

This gap between revolutionary rhetoric and geopolitical necessity would become a recurring pattern in the decades ahead—and a growing source of mistrust for China.

Outer Mongolia: The First Laboratory of Soviet Nationality Policy

Lenin’s government championed “national self-determination,” promoting this idea across the borderlands. Outer Mongolia became the first major testing ground for this policy—and one that conveniently aligned with longstanding Russian interests.

Why Outer Mongolia?

Russian influence was already entrenched, with garrisons and consulates dating to the 19th century.

Its culture and political structure differed sharply from China’s, making reintegration difficult.

It served as a useful buffer against Japan and anti-Soviet White forces.

Self-determination provided ideological cover for retaining a strategically vital region.

Thus, while preaching autonomy, Soviet Russia sent Red Army forces and advisors to shape Mongolia’s political direction. The form was revolutionary; the substance was imperial.

For China, the consequences were far-reaching:

The Beiyang government was unable to reassert authority.

The Nationalist government spent decades negotiating over a region it no longer controlled.

After 1949, the PRC ultimately recognized Outer Mongolia’s independence.

From the very beginning, the Soviets conveyed a clear message:

Political ideals were negotiable—buffer zones were not.

China as the Outer Perimeter of the Russian Civil War (1918–1922)

During the Russian Civil War, the fighting spilled into China’s borderlands. Manchuria, Xinjiang, and Mongolia all experienced incursions from White armies, the Red Army, Japanese forces, and local militias. China—fragmented and militarily weak—found itself unable to control events in its own northern frontier.

This pattern resurfaced in 1945, when Soviet troops swept into Manchuria, took over railways, shipped factories to the USSR, and sidelined the Nationalist government without resistance.

For the Chinese Communist Party, these episodes held a key lesson:

Without rebuilding national capacity, China would remain a “weak neighbor,” not an equal partner.

This conviction would later become central to China’s break with the Soviet Union in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Revolution + Empire: An Unresolved Tension

Between 1917 and 1924, Soviet Russia became the world’s only state that was anti-imperialist in its ideology while still inheriting the territorial structure of a fallen empire. China’s goals—restoring sovereignty over borderlands—directly clashed with the Soviet need to maintain strategic buffers.

Thus, when China and the USSR established formal diplomatic relations in 1924, the foundation was already unstable:

China hoped for equality and anti-imperialist partnership.

The Soviets saw a potential ally—but one whose northern regions could not be allowed to fully escape Moscow’s orbit.

From that moment forward, Sino-Soviet relations contained four elements simultaneously:

Revolutionary camaraderie

Historical distrust

Geopolitical rivalry

Border-zone competition

The split of the 1960s was the eruption of structural tensions that had existed since the beginning.

The CER and Outer Mongolia: Ideology vs Geopolitics in the 1920s

Leftist narratives often portray the 1920s as a period of internationalist harmony between China and the Soviet Union: abolition of unequal treaties, support for national liberation, cooperation with both Beijing and Guangzhou governments, and propaganda about Asian unity.

But on the ground, Soviet Russia continued to act as both revolutionary mentor and imperial heir—especially in two key regions:

The Chinese Eastern Railway (CER)

Outer Mongolia

These were the clearest manifestations of duality.

The CER: Imperial Infrastructure in Revolutionary Clothing

While the Russian Civil War raged, the CER was caught among White forces, Japanese troops, and local warlords. Chinese authorities briefly attempted to regain control. But once the Red Army regained strength, Soviet Russia sought to reestablish the joint-management system.

Why maintain a Tsarist-era privilege after proclaiming anti-imperialism?

Because the CER was strategically indispensable:

It connected Siberia to the Pacific.

It served as an alternate supply line to Vladivostok.

Russian émigré communities along the railway required Soviet oversight.

It offered Moscow a crucial lever in China’s internal politics.

Thus, Soviet Russia accepted the appearance of equality, while preserving the substance of control.

The 1930 CER Incident made this clear: when the Northeast Army attempted to nationalize the railway, the Soviet Union responded with overwhelming force and reinstated joint management. Revolutionary friendship ended where Russian strategic interests began.

This logic reappeared in 1945–46, when the Soviets seized wartime control of Manchurian railways and industry.

Outer Mongolia: From “National Liberation” to Soviet Protectorate

The Soviets’ actions in Outer Mongolia in the 1920s revealed their priorities even more starkly. After the fall of the Qing, Beijing temporarily regained authority in 1919—but Soviet Russia intervened shortly afterward, backing Mongolian revolutionaries and establishing the 1921 regime.

Although presented as “self-determination,” the new Mongolian government:

depended on Soviet military protection,

used Soviet advisors for finance, security, and intelligence,

aligned fully with Soviet strategic needs.

Suzerainty was acknowledged rhetorically to China, while separation was strengthened in practice.

This pattern—verbal support for China, concrete support for buffer zones—became one of China’s main charges against the Soviet Union during the ideological polemics of the 1960s.

The Roots of Long-Term Mistrust

These 1920s experiences left China with four lasting conclusions:

The Soviet Union inherited Tsarist strategic thinking in Manchuria, Mongolia, and Xinjiang.

Moscow viewed China through a hierarchical revolutionary lens—mentor guiding pupil.

Soviet deeds often contradicted Soviet rhetoric.

As China modernized, it became less willing to tolerate Soviet “buffer zones.”

These perceptions would later shape Mao’s insistence on independence from Moscow.

Soviet Penetration in Xinjiang (1930s–1940s): Empire Disguised as Internationalism

Soviet activity in Xinjiang is often misunderstood. It was neither a plot to carve out Xinjiang nor simply Comintern-style revolutionary exporting. It was the melding of imperial border logic with ideological tools—a continuation of Tsarist strategy under a new banner.

Xinjiang: Frontier for China, Frontline for the USSR

For China, Xinjiang was a distant, unstable frontier.

For the Soviet Union, Xinjiang was:

the eastern shield of Soviet Central Asia,

a key zone in the competition with Britain,

a lever for shaping China’s internal politics,

and a potential future buffer.

Thus, Soviet involvement was never only ideological; it was strategic.

1933–1934: Soviet “Cross-Border Aid”

As Xinjiang descended into multi-sided conflict—warlords, tribal forces, Ma Zhongying’s troops—the Soviet Union intervened with “volunteer units” that were, in reality, Red Army and NKVD detachments.

Their methods foreshadowed Soviet tactics elsewhere:

No formal annexation

No open occupation

Advisors, volunteers, and technical support

Control of key infrastructure

Air power when necessary

This was less revolutionary solidarity than temporary imperial stabilization.

A Semi-Colonial Order: Sovietized Governance Under Sheng Shicai

With Soviet backing, Sheng Shicai built a regime deeply dependent on Moscow:

Fiscal systems were supervised by Soviet advisors.

Military forces were trained and armed by the USSR.

Communications and transport linked Xinjiang to Soviet networks.

Russian-language education expanded.

Ili became a partially Sovietized region.

This created an administrative structure resembling a Soviet semi-protectorate. Sheng Shicai himself was opportunistic, switching allegiance to the Nationalists in 1942 and purging pro-Soviet forces—an event that further deepened Soviet mistrust of Chinese central authority.

Ethnicity, Migration, and Cross-Border Influence

Xinjiang’s ethnic mosaic gave Moscow additional tools:

refugee movements,

propaganda broadcasting from Central Asia,

flexible use of nationalities policy toward Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and others.

These networks allowed the Soviet Union to influence Xinjiang even when not directly intervening.

The 1941 Agreement: From Active Intervention to Strategic Waiting

After the German invasion, Moscow needed stability more than expansion. The 1941 Xinjiang–USSR trade agreement made Xinjiang heavily dependent on Soviet goods. But wartime priorities shifted Soviet policy from active manipulation to cautious maintenance.

Yet the structures built in the 1930s remained—and were revived after 1945.

Xinjiang as a Foreshadowing of the Sino-Soviet Split

Xinjiang exposed the deeper nature of the Soviet Union:

Revolutionary in words, imperial in practice.

Ideology employed flexibly—subordinate to geopolitics.

Persistent interest in shaping China’s frontiers.

Long-term Chinese distrust rooted in lived historical experience.

Thus, Xinjiang was not an isolated episode. It was the second major structural precursor—after Manchuria and Outer Mongolia—to the Sino-Soviet rupture. It taught both sides a lesson:

To China: the Soviet Union could intervene in its frontier politics with ease.

To the Soviet Union: Chinese frontiers were influenceable, but never fully controllable.

These insights shaped everything that happened when the Red Army entered Manchuria in 1945.

Part Three: Postwar Northeast and the Real Soviet Union (1945–1949)

The Soviet Entry: Not “Liberation,” but a Strategic Takeover (1945–1946)

When the Red Army swept into Manchuria in August 1945, its speed stunned both Japan and China. For the Chinese Communist Party, the moment seemed like a historic windfall: the Northeast was the industrial core of China, rich in railways, mines, arsenals, and heavy industry. Whoever controlled it would control the balance of the coming civil war.

But when Soviet troops actually entered the region, the CPC encountered a very different reality.

The Soviet Army did not behave like the “comradely liberator” the CPC had imagined. Instead, it implemented a full-scale military takeover:

Shenyang was run by a Soviet military administration.

Communication networks, rail hubs, radio stations, and warehouses were placed under Soviet control.

Industrial sites—Anshan, Fushun, Siping—were designated as Soviet military zones.

Even policing and judicial affairs were handled by temporary Soviet political-military organs.

In essence, the Soviets followed the same logic Tsarist Russia had applied in the CER zone decades earlier:

Secure control first, negotiate later; extract interests first, then consider politics.

For the CPC, this was the first direct encounter with the real Soviet Union—a powerful state with institutions, strategic memory, and clear self-interest, not an idealized socialist elder brother.

Industrial Dismantling: Soviet Priorities on Full Display

Between 1945 and 1946, Soviet forces systematically dismantled and transported large volumes of industrial equipment from Manchuria to the USSR:

Machine tool systems from Shenyang

Power plants from Fushun

Workshops from Anshan Steel

Dozens of arsenals and specialized factories

In Chinese narratives, this became known as the “dismantling of Northeast industry.” But in Soviet eyes, these were legitimate war reparations—“spoils of war” built under Japanese colonial rule and therefore fair game under Yalta’s vague provisions.

For the CPC, the implications were sobering:

The heart of China’s heavy industry was in Soviet hands.

Soviet recovery took precedence over China’s industrialization.

Aid from the USSR would be conditional, calculated, and interest-driven.

This was a formative experience. It planted two lasting convictions in CPC leadership:

China’s industrial and military modernization could never rely on the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union, though friendly, must be viewed with long-term vigilance.

These conclusions later shaped China’s determination to build its own nuclear weapons, its own heavy industry, and an autonomous defense system.

Caught Between Two Chinas: Soviet Balancing Toward the CPC and Nationalists

During the immediate postwar period, the Soviet Union clashed repeatedly with Chiang Kai-shek’s government over the handover of cities, warehouses, taxation, and troop withdrawal schedules. Soviet forces routinely stalled the Nationalist takeover of Manchurian cities, creating months-long delays.

To the CPC, watching from the sidelines, the message became clear:

The Soviet Union distrusted the Nationalists—but it also did not fully trust the CPC.

Stalin’s strategy was a classic great-power balancing act:

Recognize the Nationalist government diplomatically.

Allow the CPC to expand in the countryside, but maintain distance.

Keep the cities under Soviet control as long as possible.

Avoid committing fully to either Chinese side.

This approach forced both the Nationalists and the CPC to court Moscow while giving the USSR maximum leverage throughout the transition.

For the CPC, this was a political awakening:

The Soviet Union was not a natural ally.

It would not guarantee CPC victory.

It wanted a divided China that posed no threat to Soviet security.

This realization later shaped Mao’s stance toward Khrushchev: refusal to accept Soviet “leadership,” refusal to subordinate the CPC to the CPSU, and refusal to permit any Soviet-style “buffer zone” influence inside China.

The earliest seeds of the Sino-Soviet rift were planted here.

How the CPC Learned to See the Soviet Union: A Friend, but a Great Power First

From 1945 onward, the CPC gradually shed the romanticism of the Yan’an years. Confronting Soviet officers directly—through checkpoints, dismantled factories, restricted access to cities, and selective transfers of arms—made one thing unmistakable:

The Soviet Union was a great power before it was a socialist comrade.

The lessons the CPC drew were profound:

China’s revolution could not depend on Soviet sponsorship.

China must build its own industrial-military base.

China must pursue an independent national strategy, even within the socialist camp.

These understandings became foundational to the PRC’s later policies—and created the strategic DNA that made the Sino-Soviet split almost inevitable.

Weapons, Handover Politics, and the CPC’s First Taste of Geopolitics (1945–1948)

Soviet Aid: Not a Mission to Install the CPC in Power

Stalin’s priorities in entering Manchuria were simple:

Deter Japan

Ensure Outer Mongolia’s status

Fulfill treaty obligations with the Nationalists

Avoid confrontation with the United States

Helping the CPC seize national power was never the Soviet objective.

Thus, on the question of Japanese weapons left in Manchuria—vast arsenals, artillery, small arms, vehicles—the Soviet Union adopted a cautious stance:

“Supply the CPC if convenient, but never at the expense of relations with the Nationalists.”

This produced a contradictory situation:

The Soviet army possessed enormous stockpiles.

It refused to hand them over to the CPC unconditionally.

Much of the matériel was dismantled or shipped to the USSR.

The CPC often had to negotiate privately with local Soviet officers.

In some cases the Soviets even recaptured weapons the CPC had seized independently.

The rise of the Northeast Field Army thus came far less from Soviet largesse than from the CPC’s own improvisation, seizures, and negotiations.

Tripartite Frictions in City Handover: Moscow’s Leverage Game

The three-way contest between the Soviet Union, the Nationalists, and the CPC was most visible during the handover of Northeastern cities.

The Soviet strategy:

Formally cooperate with the Nationalists.

Quietly maintain contact with the CPC.

Retain full control until the political situation clarified.

Keep all options open.

This ambiguity allowed the USSR to exert maximum influence. For both Chinese sides, it was deeply frustrating. For the CPC, it shattered the illusion that the Soviet Union would naturally side with its ideological kin.

The Reality of Soviet Aid: Limited Transfers, Extensive Dismantling

Declassified records later confirmed what CPC leaders already knew internally:

Soviet weapons transfers were limited, selective, and never decisive.

The best Japanese equipment was retained or shipped to the Soviet Union.

Much of Manchuria’s industrial base was dismantled, not shared.

The majority of the CPC’s arsenals came from self-capture, not Soviet delivery.

This produced a dual sentiment in Mao’s mind that persisted for decades:

Reliance on the Soviet Union was necessary in the short term.

Vigilance toward the Soviet Union was necessary in the long term.

This ambivalence became a core feature of CPC strategic culture.

Outer Mongolia: The Non-Negotiable Soviet Interest (1945–1946)

Nothing revealed Soviet priorities more vividly than the settlement of Outer Mongolia’s status after World War II.

Yalta: A Pre-Decided Outcome

At Yalta, the U.S., Britain, and the Soviet Union reached a stark bargain: in exchange for entering the Pacific War, the Soviet Union would retain the “status quo” in Outer Mongolia—that is, Soviet-controlled de facto independence.

For Chiang Kai-shek, this was imposed under duress. Without Soviet participation against Japan, China risked strategic isolation. Thus, the issue was effectively removed from China’s hands.

Outer Mongolia became a non-negotiable Soviet security asset—something no Chinese government, Nationalist or Communist, could reverse.

The 1945 Referendum: A Formality Masking Reality

A referendum was held in Outer Mongolia under Soviet supervision. Unsurprisingly, the vote overwhelmingly endorsed independence. China had no observers, no leverage, and no capacity to alter the outcome.

The vote did not produce independence—it merely stamped legitimacy on what Soviet geopolitics had already decided.

For China, it was a deep humiliation: a public declaration of lost sovereignty.

For the Soviet Union, it was a legal veneer—useful internationally, but substantively irrelevant.

Outer Mongolia as a Security Structure, Not a Single Event

The geopolitical importance of Mongolia far exceeded its economic value. To the Soviet Union, it was:

the forward shield of the Soviet Far East,

a buffer against Japan and, later, the U.S.,

a barrier preventing direct contact between China and Siberia,

a vantage point for monitoring China’s north.

To China, losing Outer Mongolia meant a permanent strategic disadvantage in the northern theater—a disadvantage that would shape the border crises of the 1960s.

Chiang Kai-shek’s Forced Recognition: A Diplomatic Defeat Without Alternatives

China recognized Mongolian independence in 1946 because it had no choice. Without Soviet cooperation:

Soviet troops would not withdraw.

The Nationalists could not enter Manchurian cities.

The civil war balance would be further tilted.

This was not a diplomatic miscalculation—it was the unavoidable consequence of weakness.

For the CPC, watching this unfold delivered a brutal lesson:

Without strength, sovereignty cannot be defended. Without sovereignty, diplomacy is powerless.

This insight became a pillar of later PRC strategy—especially in nuclear development and defense planning.

CPC Silence on Mongolia: Not Ignorance, but Strategy

The CPC publicly avoided criticizing Mongolia’s separation. The reason was simple: power determines borders. Without strength, reclaiming Mongolia was impossible; with strength, China would rely on its own capabilities rather than Soviet goodwill.

Privately, CPC leaders reached a stark conclusion:

The Soviet Union would help China—but only up to the point where China remained non-threatening.

This judgment was repeatedly confirmed in later decades, from the nuclear cooperation disputes to the polemics to the border clashes.

The Structural Significance of Outer Mongolia: Why China and the USSR Could Never Be True Allies

Mongolia’s final separation in 1945–46 crystallized an irreconcilable contradiction:

For the Soviet Union, Mongolia was an essential buffer.

For China, Mongolia was a historic frontier and a national memory.

There was no compromise between these positions.

Thus:

Soviet interests always outranked ideology.

Security trumped socialist brotherhood.

Russian imperial logic survived beneath Soviet internationalism.

China could never be permitted to grow powerful in the north.

Outer Mongolia was not the origin of the Sino-Soviet split—it was its structural precondition.

Its shadow fell across every later dispute: the ideological polemics, the nuclear quarrel, the missile deployments in Mongolia, the Ussuri clashes, and the Zhenbao Island firefight.

It was not merely a chapter in history; it was an enduring fault line—one that shaped the fate of the two socialist giants.

Part Four: The Peak of the Alliance—and the Cracks Beneath It (1949–1956)

Mao’s Visit to Moscow (1949–1950): Alliance Born, Fault Lines Revealed

Mao Zedong’s first trip to the Soviet Union is often remembered as a grand moment of socialist unity. In reality, it was the first major test of power between a rising revolutionary state and the established center of the socialist world. The visit produced both the high point of the Sino-Soviet alliance and the earliest visible fractures that would later split it apart.

At the heart of the visit were four sobering realizations:

The Soviet Union did not see China as an equal partner, but as a new state that required supervision and constraint.

Mao discovered, for the first time firsthand, that the Soviet Union was not the flawless socialist utopia he had long imagined.

Outer Mongolia proved to be a strategic red line for the Soviets, instantly exposing the two sides’ divergent national interests.

The question of “who leads whom” already surfaced, foreshadowing the coming ideological and political struggle for authority in the socialist camp.

Understanding the Sino-Soviet split requires starting with Mao’s sixty-six uneasy days in Moscow.

The Delayed Invitation: Stalin’s Suspicion of the New China

China declared it would “lean to one side” toward the Soviet Union immediately after the proclamation of the PRC. But the Kremlin hesitated.

Stalin questioned:

whether the CPC would follow Soviet direction,

whether Mao intended to carve an independent path,

and whether China might become “another Yugoslavia.”

Thus, the Sino-Soviet relationship began with psychological inequality: China eager to seal the alliance, the Soviet Union wary and calculating.

This tension framed the entire Moscow visit.

Moscow’s Cold Reception: Mao’s Long Wait

Mao arrived expecting warmth and revolutionary enthusiasm. Instead, he was met with silence, delays, and formality.

Stalin refused to meet him immediately.

Meetings lacked substance for weeks.

Mao was housed in an isolated villa outside the city.

The Soviets even proposed keeping the old 1945 treaty signed with the Nationalists.

Mao joked bitterly:

“I did not come as a guest—I came to serve a sentence.”

Behind that remark was a painful realization:

New China had not been welcomed as an equal socialist state but as a junior member still under inspection.

Outer Mongolia: The First Strategic Collision

Mao raised the Outer Mongolia issue for one reason: it represented national humiliation. From Chinese memory, the sequence was clear:

1911: autonomy after the Qing collapse

1921: Soviet intervention

1945: Soviet-supervised referendum and independence

Mao approached the matter cautiously, probing whether Mongolia’s status might be reconsidered in the future.

Stalin’s answer was absolute:

Mongolia was a necessary Soviet security zone.

Its independence was irreversible.

China should feel “grateful” that the USSR was guarding its northern flank.

The message was unmistakable:

Ideology ends where Soviet geopolitical interests begin.

For Mao, this was the moment he first confronted the Soviet Union’s “imperial nature.” The USSR’s bottom line in Asia was non-negotiable, and China was itself considered a potential future threat.

This insight planted the first structural seed of mistrust.

Treaty Negotiations: Equality vs. Subordination

The Outer Mongolia dispute revealed Soviet red lines; treaty negotiations revealed Soviet expectations. Stalin initially wanted China simply to accept the old, unequal treaty with minor adjustments.

Mao refused outright.

He insisted on:

abolishing the 1945 treaty,

signing a new one between two sovereign states,

and formal recognition of China’s equality.

The final treaty—Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance—was a compromise, but the negotiation process made clear:

The Soviet Union expected obedience.

China expected recognition as an independent great power.

This dispute over authority would later explode in the ideological polemics of the 1960s.

Aid and Control: Help with Conditions Attached

Soviet support—loans, factories, advisors, military equipment—was enormous. But every element carried a logic of control:

Loans mandated Soviet equipment purchases.

Advisors held authority over major projects.

Trade and shipping routes operated through Soviet channels.

Certain bases and ports remained under Soviet influence.

Mao understood the political meaning of this:

Aid built capability, but dependence eroded autonomy.

The price of help was vulnerability.

This dynamic later drove Mao toward the Great Leap Forward, subsequent economic experiments, and the push for independent nuclear capability.

Why Mao’s Visit Marked the Structural Beginning of the Split

The visit exposed three contradictions no ceremony could mask:

Geopolitics: The Soviet Union maintained imperial interests.

Leadership: Both sides sought ideological authority.

Security: Neither trusted the other’s long-term intentions.

This visit was not a celebration of unity—it was the quiet beginning of a future rupture.

The Korean War (1950–1953): Alliance Tested, Contradictions Exposed

If Mao’s visit created the alliance, the Korean War put it under fire. The war brought China and the Soviet Union into the closest military cooperation in their history—and revealed, with brutal clarity, how different their strategic goals truly were.

The war became a “great revealing mirror,” stripping away ideological illusions and exposing raw national interests.

Two Different Objectives from the Start

For the Soviet Union:

Pressure the United States in East Asia

Use Korea as a strategic experiment

Avoid direct confrontation with U.S. forces

Let China bear the cost if escalation occurred

For China:

Prevent U.S. troops from reaching the Yalu River

Protect Manchuria’s industrial heartland

Secure the borders of the newly founded PRC

Thus, when war broke out, two logics collided:

The Soviets expected China to fight.

China expected Soviet solidarity.

This disconnect shaped the entire conflict.

Stalin’s Strategy: Encourage China, Avoid Risks

As North Korea collapsed, Stalin pressed China to intervene—while refusing to send Soviet ground forces.

His logic:

Support the war from behind.

Provide aircraft and advisors.

Avoid direct U.S.–Soviet confrontation.

Ensure China carried the main burden.

For China, this was unavoidable but deeply frustrating. The choice was stark:

enter the war and bear massive costs, or

risk U.S. troops directly on China’s border.

China entered the war—but remembered the asymmetry.

First Structural Crack: Command and Autonomy

The Soviets attempted to impose strategic preferences through advisors:

defensive posture,

cautious operations,

limiting escalation,

and preserving Soviet image abroad.

China preferred:

mobile warfare,

decisive offensives,

political mobilization,

and preventing U.S. advances toward the Yalu.

The two sides were operating from fundamentally different military cultures. Soviet advisors often saw Chinese commanders as reckless; Chinese commanders saw Soviet advisors as detached from battlefield reality.

The mistrust deepened.

Second Crack: War Aid and Debt

Soviet equipment was indispensable—but it was not free.

Everything was loans:

aircraft,

tanks,

artillery,

fuel,

ammunition.

China paid enormous costs—financially and in blood. The Soviets believed they had been generous. The Chinese believed they bore disproportionate sacrifice.

This grievance quietly hardened inside the CPC leadership.

Third Crack: Limited Soviet Air Support

Soviet pilots fought in Korea—but under strict restrictions:

no flying deep into Chinese territory,

no acknowledgment of Soviet involvement,

operations confined to the “MiG Alley,”

Soviet pilots disguised as Chinese or Korean.

To China, this conveyed a clear message:

The Soviets would aid China, but only within their own safety margin.

China was grateful, but also resentful.

Armistice Negotiations: Divergent Endgames

China wanted an early end to preserve strength.

The Soviet Union preferred prolonged negotiations to keep U.S. forces tied down.

Once again, national goals diverged.

Why the Korean War Became a Rehearsal for the Split

The war created five irreversible strategic divergences:

The Soviet Union would not risk direct war with the U.S. for China.

Aid would always come with political strings.

China and the Soviet Union had different visions of security.

China’s sacrifices were vastly greater than the Soviet Union’s.

Ideology could not erase geopolitical reality.

After 1953, the alliance remained strong—but the fractures were already growing.

Soviet Aid and Its Dual Nature (1953–1956): Construction and Constraint

The death of Stalin brought a new phase of cooperation. Soviet experts arrived en masse; massive industrial projects began; the alliance reached its highest level of activity.

But beneath the surface, the seeds of future confrontation were germinating.

The Soviet Union Needed China—but Sought to Shape It

With the post-Stalin leadership seeking stability, China became vital:

as an industrializing partner,

as a counterweight in Asia,

as proof of socialist vitality.

But the USSR simultaneously attempted to embed China in a Soviet-centered system—economically, industrially, militarily, and ideologically.

China accepted assistance, but resisted subordination. This duality became the central tension of the 1950s.

The 156 Projects: Foundation of Industry, Framework of Dependence

The “156 projects” formed the backbone of China’s early heavy industry. They were transformative—but they were also built entirely on Soviet standards.

Their structure meant:

China’s industrial system was aligned to Soviet technology and processes.

Installation, equipment, and training required Soviet approval.

Soviet experts controlled key positions in factories and research institutes.

Industrialization advanced rapidly—but dependence deepened.

China’s leaders recognized both truths simultaneously.

Loans and the Economic Web of Control

Soviet loans came with strict conditions:

equipment must be purchased from the USSR,

imports from third countries were restricted,

repayment often required Chinese resources.

This was not exploitation—it was an imperial logic repackaged under socialism:

assist, but ensure strategic dependence.

This financial structure later became a weapon during the breakdown of relations.

Military-Industrial Aid: Cooperation with Limits

Military cooperation was extensive: naval shipyards, aviation institutes, missile research centers. Yet Soviet restrictions remained:

key technologies withheld,

core blueprints not transferred,

strategic advice bordering on intervention.

Mao summarized the gap succinctly:

“The Soviet Union helps us, but cannot lead us.”

This formed the basis of future conflict over nuclear weapons and defense autonomy.

Ideology: Cooperation on the Surface, Competition Underneath

Both sides appeared united, but beneath the slogans lay rivalry:

Who interpreted Marxism correctly?

Who represented the future of revolution?

Who led the socialist world?

China viewed its revolution as more authentic than the Soviet experience.

The Soviet Union viewed itself as the unquestioned center.

This ideological tension erupted after 1956—but its roots were already deep.

The Dual Structure of Relations (1953–1956)

Visible layer: cooperation, warmth, shared propaganda, booming industrial projects.

Hidden layer: mutual vigilance, sovereignty sensitivities, fear of shaping and control.

Two great powers were cooperating—but watching each other carefully.

This made a major clash inevitable.

The Joint Fleet and the Long-Wave Radio Station (1954–1955): The First Open Sovereignty Clash

These two disputes marked the first explicit rejection of Soviet proposals by the PRC—and the moment both sides realized the alliance had limits.

The Joint Fleet Proposal: Bases in China, Command in Soviet Hands

In 1954, the USSR proposed a joint Pacific fleet:

based largely in Chinese ports,

under joint (effectively Soviet) command,

with Soviet officers at the helm.

For China, this was unacceptable:

It amounted to ceding control of China’s coastline.

It undermined China’s newly restored sovereignty over Lushun and Dalian.

It placed China’s navy under a foreign command structure.

Mao’s instruction was unambiguous:

“We cannot have a joint fleet.”

This was the first time China explicitly refused a major Soviet military arrangement.

The Long-Wave Radio Station: Strategic Communications Under Foreign Oversight

Long-wave communication was the backbone of Cold War strategic command. The Soviet proposal:

build it in China,

but run it with Soviet personnel,

under Soviet jurisdiction.

To China, this was effectively a military command node inside Chinese territory.

Control of communications was control of sovereignty.

China rejected the demand.

The Soviet leadership was stunned: China had defied the “center” for the first time.

Why These Conflicts Were Historic Turning Points

These disputes revealed five structural truths:

China refused to be militarily incorporated into a Soviet-led bloc.

Geopolitical interests outweighed ideological unity.

China concluded it must accelerate its own defense development—including nuclear weapons.

Khrushchev began viewing China as “unmanageable.”

The essence of the later Sino-Soviet split was now visible:

the Soviet Union sought leadership; China demanded autonomy.

These were the early echoes of the ideological polemics, the nuclear quarrel, the 1960 expert withdrawal, and ultimately the Zhenbao Island conflict.

Part Five: Ideological Rupture (1956–1960)

From Structural Divergence to Open Confrontation

The 20th CPSU Congress (1956): When the Alliance’s Foundations Shifted

The 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was far more than an internal Soviet affair. It marked the moment when the underlying alignment between China and the Soviet Union began to unravel. Until 1956, their contradictions were mostly structural but hidden. After the 20th Congress, they became overt and ideological.

This congress reshaped the international communist movement, redefined hierarchy within the socialist world, and made both parties realize—each for the first time—that their interests were not naturally aligned.

In short:

China realized the Soviet Union was not a “natural leader.”

The Soviet Union realized China was not a state that could be easily absorbed into a Soviet-centered order.

The split did not begin in 1960—it began here.

The Secret Speech: De-Stalinization and China’s Crisis of Legitimacy

When Khrushchev denounced Stalin’s crimes—mass repression, dictatorship, suppression of collective leadership—the shockwaves reached far beyond Moscow.

For China, Stalin was not merely a Soviet figure; he was the model for:

centralized state power,

the planned economy,

industrialization strategy,

party-led control of society,

class struggle as governance doctrine.

China had built its new state largely on a Stalinist blueprint. Thus, Khrushchev’s denunciation sounded less like Soviet “self-correction” and more like an attack on China’s own governing foundation.

Beijing’s immediate concerns were profound:

Would the Soviet Union later criticize China the same way?

Would de-Stalinization weaken its own political legitimacy?

Would the Soviet Union still treat China as an equal?

For the first time since 1949, ideological unity began to fracture.

“Peaceful Coexistence”: A Diplomatic Earthquake

The second major shift at the 20th Congress was Khrushchev’s strategic doctrine of peaceful coexistence with the West.

To the USSR, this meant:

avoiding nuclear war,

easing Cold War tensions,

focusing on economic recovery.

To China, it meant something else entirely:

the Soviet Union retreating from revolutionary leadership,

reduced support for anti-imperialist movements,

a potential pullback in Soviet assistance,

and a downgrading of China’s international value.

For China—fresh from the Korean War and still consolidating its state—Soviet détente with the West looked like abandonment.

Most importantly, Khrushchev sought to universalize peaceful coexistence across the socialist camp.

China saw this as:

The Soviet Union attempting to reshape the entire communist world in its own image.

Redefining the Socialist Camp: China Refuses a Second-Class Role

The 20th Congress framed the USSR as the mature, leading socialist state, with other countries expected to follow its model.

Eastern Europe accepted this hierarchy.

China did not.

China’s internal thinking hardening quickly:

We are not a Soviet appendage.

We have our own revolutionary legitimacy.

We will not accept a Soviet “guiding role.”

Socialism has multiple paths—not only the Soviet one.

This was the birth of China’s vision of an independent socialist line.

The Soviet Union had not expected such confidence—or defiance—from Beijing.

Poland and Hungary (1956): The First Public Divergence

The turmoil in Poland and the revolution in Hungary brought the Sino-Soviet fault lines into open view for the first time.

For the Soviet Union:

Eastern Europe was a security perimeter. Any instability was a direct threat to Soviet survival.

For China:

If socialist states solved internal crises only through Soviet force, they were reduced to protectorates, not sovereign countries.

China’s reactions were nuanced but revealing:

Supported limited autonomy in Poland

Opposed Hungary’s attempt to break away

Opposed the idea of Soviet over-intervention

Two takeaways reshaped China’s perception:

The Soviet Union’s “peaceful coexistence” was tactical, not principled.

Intervention in Hungary revived China’s deepest historical fear: foreign domination under socialist banners.

For Mao, Hungary raised a chilling question:

If China diverged from Moscow, would the Soviet Union consider intervening?

The seeds of distrust deepened.

The Core Consequence of 1956: China Realizes the USSR Is Not a Reliable Revolutionary Partner

Three irreversible fissures emerged:

Different ideological priorities

USSR: stability and coexistence

China: revolution and anti-imperialism

Different national interests

USSR: global balance and avoiding conflict

China: reshaping the global revolutionary landscape

Different visions of leadership

USSR: unquestioned center

China: rising challenger

These cracks were temporarily masked by continued cooperation—but they were already irreversible.

The 1957 Moscow Conference: The First Open Battle for Leadership

The 1957 Conference, held for the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution, was intended as a Soviet display of dominance. Instead, it became the first large-scale confrontation between China and the USSR over leadership of the socialist world.

The Soviet Plan:

restore authority after Eastern Europe’s upheaval

impose “peaceful coexistence” as universal doctrine

reaffirm the USSR as the sole center

prevent China from becoming an independent pole

China’s Plan:

challenge Soviet supremacy

reject imposed ideological lines

assert the legitimacy of violent revolution

promote a multipolar socialist movement

gain equal status in the camp

This was not alliance management.

This was a power struggle.

The Central Dispute: Peaceful Transition vs. Revolutionary Violence

The USSR insisted socialism could be achieved through parliament in some capitalist states.

China saw this as ideological betrayal.

Mao responded bluntly in Moscow:

Imperialism would not abandon war.

Class struggle remained the driver of history.

Parliamentary transition was an illusion.

This was a direct rejection of Soviet attempts to redefine global communism.

Behind Mao’s argument was a deeper principle:

The Soviet Union has no right to dictate the path of world revolution.

China’s Breakthrough: Forcing the USSR to Accept “Equality Among Parties”

China insisted on adding four principles to the final declaration:

Equality among socialist parties

No interference in internal affairs

Violent revolution remains valid

No “leader country” in the movement

The Soviets reluctantly agreed.

This was a historic shift:

China went from student → equal → ideological competitor

The USSR realized Mao was not manageable

Mutual suspicion became institutional

The split had not yet exploded—but the foundation of unity was gone.

The Breakdown of Nuclear Cooperation (1957–1959): Collision of Core Interests

If 1956 fractured ideology, and 1957 fractured leadership, then 1959 fractured national security. That made the split irreversible.

1957: Nuclear Cooperation Begins in a Moment of Political Convenience

The Soviets agreed to:

provide China with a model atomic bomb,

transfer some key technologies.

China saw nuclear weapons as essential to sovereignty.

The USSR saw nuclear sharing as a temporary political concession.

Both sides entered the arrangement with different goals.

1958: The Great Leap Forward and the Taiwan Strait Crisis Change Everything

Two events alarmed Moscow:

The Great Leap Forward

China’s radical domestic program made Khrushchev question Mao’s judgment.Eighth Bombardment of Kinmen

China ignited a crisis with the U.S., forcing the USSR into tense backchannel diplomacy.

Moscow’s conclusion:

China was unpredictable

China might drag the USSR into war

A nuclear-armed China could threaten the entire balance of the socialist camp

This was the turning point.

1959: The USSR Tears Up Nuclear Agreements

Under the guise of “preventing nuclear proliferation,” Moscow canceled the transfer of:

the atomic bomb prototype,

corresponding blueprints,

further key technologies.

The real logic was simple:

The Soviet Union could not accept a powerful, independent China with nuclear weapons.

This was not a misunderstanding—

it was a direct collision of core national interests.

China’s Reaction: Shock, Fury, and the Decision for Full Autonomy

Beijing immediately grasped the political message:

The USSR wanted to contain China

Nuclear dependence was a form of control

China’s security could only rest on self-reliance

Mao and Zhou were explicit:

“The Soviets want to choke us—they cannot.”

“Nuclear weapons must come from ourselves.”

From 1959 on, China committed to:

Independent nuclear development

Full strategic autonomy

Viewing the USSR as a potential threat

The consequences would echo all the way to the 1969 Ussuri River conflict.

Khrushchev’s Miscalculation

Moscow misjudged two things:

China’s political will

China detonated its own bomb by 1964.China’s historical memory

As a former victim of great-power interference, China reacted violently to Soviet manipulation.

These errors pushed China decisively toward its own path.

1959 as the Real Point of No Return

Many assume the split began in 1960 with the withdrawal of Soviet experts or in 1963 with the polemics.

But structurally, the essential break occurred in 1959:

China and the USSR diverged on nuclear strategy

Their security interests became incompatible

Mutual suspicions became openly acknowledged

Two centers emerged in the socialist world

From that moment, the alliance could no longer be repaired.

Conclusion: Nuclear Rupture Turns Ideology into Geopolitics

The nuclear break transformed the relationship entirely:

For China: nuclear weapons meant sovereignty, survival, and independence.

For the Soviet Union: nuclear weapons meant hierarchy, control, and leadership.

There was no middle ground.

The Sino-Soviet split was now inevitable.

Everything afterward—the polemics, the expert withdrawal, Zhenbao Island—was an acceleration of a break already sealed.

Part Six: The Border Cold War and Total Hostility (1960–1969)

The 1960 Expert Withdrawal: From Dangerous Alliance to Open Hostility

In summer 1960, the Soviet Union abruptly pulled all of its experts out of China—tearing up contracts, halting projects mid-construction, seizing blueprints, and cutting off equipment deliveries. To China, the shock felt like betrayal; to Moscow, it was an act of self-preservation. In structural terms, the withdrawal was not a sudden impulse but the culmination of tensions that had been accumulating for years.

The retreat signaled a fundamental shift:

The two largest socialist states had moved from uneasy partnership into declared antagonism.

The withdrawal marked:

the first major rupture between great powers within the socialist world,

the beginning of China’s enforced isolation,

and the launch of China’s independent military-industrial and nuclear programs.

Understanding its meaning requires viewing it through four lenses:

An ideological split pushed into the open

Soviet mistrust of China’s domestic and strategic line

Irreconcilable national interests

Enduring consequences for China’s development and foreign policy

Ideology Turns Into Open War (1956–1960)

The seeds were planted in 1956 at the 20th CPSU Congress. Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization, his embrace of peaceful coexistence with the West, and his insistence that global war was avoidable contradicted Mao’s worldview on every front.

By 1959, the split was public:

China accused the USSR of “revisionism.”

The USSR accused China of “leftist adventurism.”

This was not a debate over policy details—it was a collision over the future of socialism itself.

By 1960, the dispute spilled into the open. China challenged Soviet leadership in the international communist movement; Moscow saw Beijing as attempting to form a rival center of revolution.

The expert withdrawal was Moscow’s institutional way of expressing:

“You no longer follow our line. You will no longer receive our support.”

Soviet Fear of China’s Trajectory

The Great Leap Forward and the people’s communes frightened Soviet observers:

wildly inflated grain production claims,

backyard steel furnaces,

sweeping changes to rural and social organization,

Mao’s belief in accelerated historical development.

To Moscow, China no longer looked like a stable socialist partner—it looked dangerous.

These fears intensified after the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis (1958). China’s bombardment of Kinmen risked pulling the Soviet Union into direct conflict with the United States—precisely when Khrushchev was promoting détente.

For the Soviet leadership, the calculation was simple:

China’s revolutionary impulses threatened Soviet global strategy.

The USSR refused to be dragged into another war.

The withdrawal was a way of cutting the cord.

Conflicting National Interests: The Alliance Collapses in Substance

By 1960, three fundamental contradictions had taken shape:

Leadership of the Socialist World

China demanded autonomy among communist parties.

The USSR insisted on unified Soviet leadership.

Security in Asia

The USSR favored negotiation, stability, and avoidance of conflict.

China saw Asia as a revolutionary battlefield.

Strategic Attitudes Toward the United States

The USSR sought détente.

China saw the U.S. as the core enemy requiring constant struggle.

The alliance no longer had a realistic foundation.

The expert withdrawal simply made the divorce public.

A Withdrawal With Punitive Force

The way the Soviets left was devastating:

1,390 experts departed almost overnight.

Contracts were broken midstream.

Technical drawings vanished with departing teams.

Half-built production lines were dismantled.

Crucial machinery was reclaimed or never delivered.

Nuclear cooperation stopped completely.

For the Soviets, this was risk management.

For China, it was humiliation.

Beijing concluded the USSR had treated it like a subordinate state, not an equal partner.

Emotionally and politically, the break became irreversible.

China’s Response: Trauma, Resolve, and the Path to Autonomy

Short-term consequences were severe:

Projects across the country stalled.

Technical systems collapsed.

The Great Leap Forward famine deepened.

Propaganda intensified into full anti-revisionist mode.

Nuclear research had to start from scratch.

But the long-term impact was transformative. China internalized four lessons:

Dependence on any great power is dangerous.

Nuclear weapons must be developed independently, at any cost.

China must craft a fully autonomous foreign policy.

Sino-Soviet friendship was over—permanently.

The withdrawal was China’s “painful weaning,” reshaping its industrial and strategic path for decades.

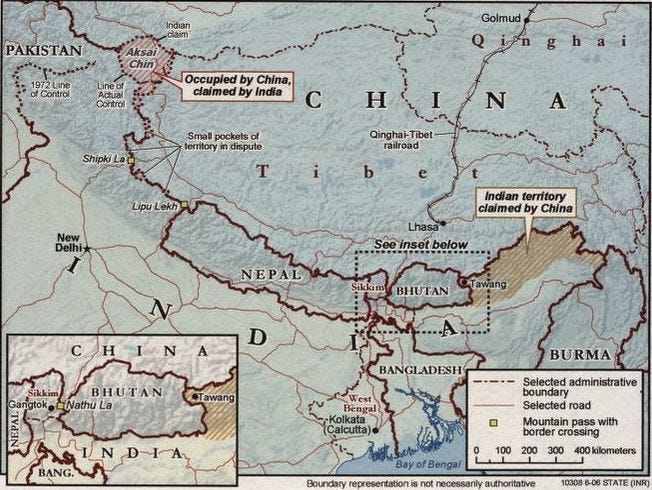

1962: The Sino-Indian War and the Mask Falls

The border war with India became the moment China fully realized:

The Soviet Union would not stand with China on essential security issues.

What alarmed Beijing was not Soviet neutrality, but the reality behind it.

Why the USSR Tilted Toward India

Khrushchev wanted détente with both India and the U.S.

Supporting China risked global escalation.

The USSR feared China’s “military adventurism.”

India was diplomatically valuable and a major arms customer.

Thus, Moscow:

refused to back China on the McMahon Line,

continued supplying India with arms,

pressured China to accept ceasefire and negotiations,

suppressed China’s positions in international forums.

The message was unmistakable:

China’s interests were expendable. India’s were not.

A Psychological Turning Point

The war triggered China’s first realization that:

The USSR viewed China as unpredictable,

prioritized its own global strategy over socialist solidarity,

and might someday treat China as an adversary.

This revelation set the trajectory for:

the 1963 open polemics,

the race to complete the nuclear program,

resistance to Soviet security proposals,

border militarization,

and eventual rapprochement with the United States.

If 1960 marked the political rupture,

1962 marked the strategic rupture.

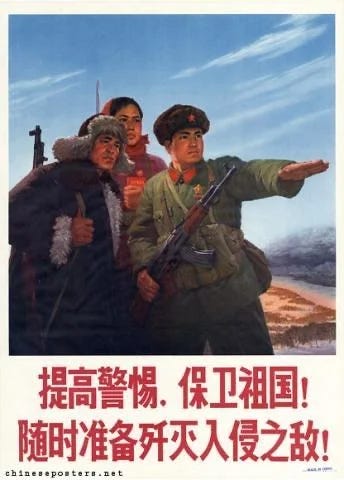

Outer Mongolia Missile Deployment (1964–1965): From Brother to Nuclear Threat

The deployment of Soviet missiles in Outer Mongolia was the decisive moment when China concluded:

“The USSR might attack us.”

This transformed bilateral hostility from political to military.

The Century-Long Logic Behind the Missiles

Outer Mongolia had been a Russian/Soviet buffer zone since the 19th century—first defensive, then protective, and now offensive.

By the 1960s, as Sino-Soviet relations deteriorated, the USSR revived old imperial patterns:

Outer Mongolia as strategic depth,

a shield against China,

and now a forward base for nuclear forces.

The difference was the scale:

This time, it was nuclear.

R-12 Deployment: Beijing Within Strike Range

The deployment of R-12 (SS-4) missiles placed major Chinese cities—including Beijing, Tianjin, Lanzhou, and Shenyang—within nuclear range.

This was unprecedented. China now faced a nuclear threat not only from the United States, but from its former ally.

Combined with:

Soviet objection to China’s nuclear tests,

rapid troop buildup in Siberia and Mongolia,

intensified border reconnaissance,

and escalating ideological attacks,

the strategic meaning was unmistakable.

China’s Counterstrategy: Prepare for the Worst

Beijing responded with sweeping national measures:

Third Front Construction

Shifting heavy industry into remote inland regions to shield it from missile attacks.Full-scale border fortification

Reinforcing Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and the Northeast with armored and mobile units.Accelerated nuclear program

“Two bombs, one satellite” became a matter of survival.Ideological mobilization

Preparing the public for confrontation with the Soviet Union.

China concluded that the USSR had reclassified China from “ally” to “potential enemy.”

Reconciliation became impossible.

1969: Zhenbao Island and Tielieketi—The Edge of Hot War

The border clashes of 1969 were not accidents or rogue patrol skirmishes. They were the ignition point of twenty years of structural antagonism compressed into a few square kilometers of river ice.

Why Zhenbao Island Became the Flashpoint

By the late 1960s:

Soviet troops along the border had surged into the hundreds of thousands.

China believed Moscow was considering surgical strikes on Chinese nuclear sites.

Propaganda on both sides framed the other as imperialist.

Border patrol confrontations became daily occurrences.

Zhenbao Island—small, frozen, and strategically symbolic—became the point where two opposing security systems collided.

March 2, 1969: China Strikes First

Academic consensus now holds that China launched a pre-planned ambush, not as provocation but as a strategic demonstration:

to break Soviet deterrence,

to counter repeated Soviet encroachments,

to show China would fight if pushed.

The ambush inflicted heavy Soviet casualties and shocked Moscow.

Soviet Reaction: Troops, Armor, and Nuclear Posturing

The Soviet Union escalated swiftly:

massive reinforcements across the Siberian and Mongolian fronts,

heightened nuclear alert discussions within the Politburo,

quiet inquiries to Washington about reactions to strikes on Chinese nuclear facilities,

intensified border patrols and propaganda.

For China, this confirmed the worst-case scenario:

The Soviet Union might actually initiate war.

Tielieketi: The Conflict Expands Westward

In August 1969, another clash erupted in Xinjiang. With deeper troop involvement and a higher risk of escalation, it demonstrated that:

Sino-Soviet hostility now spanned the entire border—from the Ussuri to the Ili.

Strategic Consequences: A New Cold War Triangle

The 1969 battles reshaped the geopolitical landscape:

An irreversible Sino-Soviet rupture

Not ideological or political, but military.China reorients its strategy

fortified interior industrial bases

accelerated nuclear and missile development

reinforced border commands

Opening to the United States becomes feasible

Zhenbao Island made Sino-American rapprochement strategically inevitable.East Asia’s Cold War structure transforms

The U.S.–China–Soviet triangle replaces the U.S.–USSR bipolar structure.

Zhenbao Island was not a border incident.

It was the ignition point of a new Asian geopolitical order.

Conclusion: The Explosion of a Century-Long Structure

The 1969 clashes were the visible flames of a long historical fuse:

19th-century unequal treaties

Soviet security logic in Outer Mongolia

postwar rivalries in Manchuria